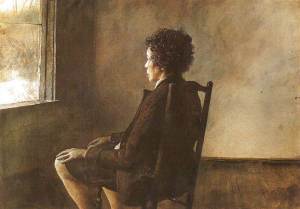

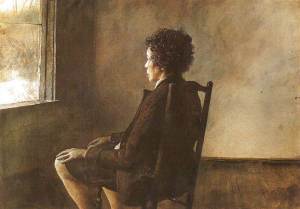

Andrew Wyeth's paintings always evoke melancholy

This morning I read through the New York Times weekend magazine, as I often do on Saturday or Sunday mornings. They have excellent longer articles and essays, well written and thought provoking.

This weekend they had an article called Depression’s Upside, outlining a recent study by psychologists who were trying to figure out the evolutionary purpose of depression–an illness that, for all intents and purposes, seems anti-evolutionary. Since people with depression seem to exhibit behaviors that endanger rather than perpetuate the species (they have decreased appetite, less interest in sex and social engagements). Depressed people also tend to ruminate endlessly (to ruminate is to analyze over and over the same details of the same problem), which is usually seen as a complete waste of mental energy, and often has the effect that people get stuck in a pattern, unable to move on from their depressive state.

The two scientists didn’t want to attribute depression to an evolutionary accident. Because depression is so prevalent in modern culture, as they eloquently state: “[…] the modern human mind is tilted toward sadness.”

The study looked at what could be cognitive upsides of depression, and in particular at these “ruminative tendencies.” The scientists found that there is a correlation to increased cognitive activity in the area just behind the forehead (the left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex or VLPFC) in people who are depressed. This increased activity actually corresponds to higher levels of awareness, attentiveness and better analytical focus. Depressed people, according to this study, are able to solve complex problems and make better decisions than non-depressed people. “[…] negative moods lead to better decisions in complex situations.”

What these scientists deem the “analytic-rumination hypothesis” looks at the sunny side of darkness. Accordingly, my anti-social tendencies can actually keep me from being distracted by the outside world, allowing me to focus on my problems as well as my pursuits. They site Darwin as an example, who suffered all his life from severe bouts of depression and never believed that he would amount to anything.

What I find interesting is their question “Why is mental illness so closely associated with creativity?” To quote further:

Andreasen argues that depression is intertwined with a “cognitive style” that makes people more likely to produce successful works of art. In the creative process, Andreasen says, “one of the most important qualities is persistence.” Based on the Iowa sample, Andreasen found that “successful writers are like prizefighters who keep on getting hit but won’t go down. They’ll stick with it until it’s right. […] Successful individuals were eight times as likely as people in the general population to suffer from major depressive illness.

Good news for those of us who frequently suffer from depression?

Up In the Studio by Andrew Wyeth

I have had one or another forms of depression since 1999, sometimes it has been much more severe than others, and very often it’s tied to a significant life change or the death of a loved one (both of which the scientists in the study say is often a cause for depression). And I have found that these periods can be alternately incredibly fruitful on a creative level as well as incredibly debilitating.

The decreased interest in social interactions, while putting me into an introspective (and thus often very creative) mood, can also lead to a feeling of extreme isolation, that dead-ends in an almost vegetable state (=can’t get out of bed, can’t do anything). I work best in solitude, and I find that I can handle, and actually prefer, much more solitude than many of my friends and acquaintances seem to prefer. But when that solitude affects my ability to function on a simple maintenance level (i.e. not eating, not sleeping, etc.), this is where creative productivity ceases and destructive behaviors set in. So it’s a two-edged sword.

What I also find interesting from this article is the concept of uninterrupted focus on complex analytic ideas in people with depressive tendencies. Again, speaking from my own experience, I find that this is very often the case with my own thinking. It is often in the summer time, when the weather is beautiful and I am feeling happy, that I have the hardest time being creative and writing or drawing or learning new music. Probably because I find so many (good) reasons to be distracted. Whereas when I’m very moody, I have so many roiling emotions and acute, almost painful sensory intake that I have to put them into some kind of creative expression or I feel like I will explode. At times like this, I can sit down and work without distraction for days, focusing, solving problems, churning out page after page of work. Even if I’m miserable.

Andrew Wyeth house

This heightened attention to sensory information is probably what creates so many writers out of depressed people, and I found that point in the article quite important. To write well, one first has to see, is the old adage. Show, don’t tell, is another angle on the same point. You don’t simply write that something is “beautiful.” This doesn’t reach out and grab the reader–this doesn’t draw them into the world that you are creating. To do this, you have to describe it in such a way that the reader can see it, smell it, watch the liquid way that it moves, taste the substance, almost put it between their finger tips, feel the emotion of the moment in its urgency and infinite possibilities–and in that way, they will know that you (the writer) think that it’s beautiful. To be able to do that well, one must be acutely aware of small details which, according to this study, one has a higher chance of being if one is depressed.

Though I have many questions about how relevant this theory is for non-event-related depressions, or depressions that are so painful that a person can’t do anything, and though I don’t want to romanticize depression (nor, I think, do the scientists of that study), I found it to be a refreshing look at an illness that many in modern culture have stigmatized. We want so often to be rid of our sadness. Sadness, anger, disinterestedness—these negative emotions and states are too often dismissed or repressed as being unacceptable.

On this topic, I read a brilliant essay called “Anger and the Gentle Life” (scroll down to see the chapter of this topic) in a book called Awakening the Heart: East/West Approaches to Psychotherapy and the Healing Relationships. (Recommended to me by my wonderful Seattle buddy Jason). It showed me a new way of approaching so-called negative feelings, and allowing them a space to ruminate and work themselves out.

And that should be one eventual goal of rumination, in my opinion—to work things out. To analyze and divide something over and over again in order for it to make sense so you can move on to the next bit. Getting stuck—endlessly dividing—may only leave you with countless tiny bits of nothing. Like a human shredder of thoughts.

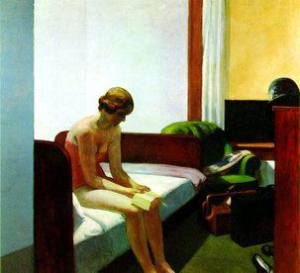

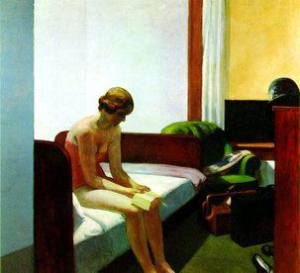

Now, on to another day of avoiding other people and working on my melancholy creative pursuits. Here are some other images that I love that also have this wonderful feeling, perhaps also suggesting that their creators knew that mood as well:

Andrew Wyeth "Helga"

Andrew Wyeth "Fisherman"

Andrew Wyeth "Wind from the Sea"

Edward Hopper "Hotel Room"

Edvard Munch